The 2024 Atlantic Hurricane Season Outlook

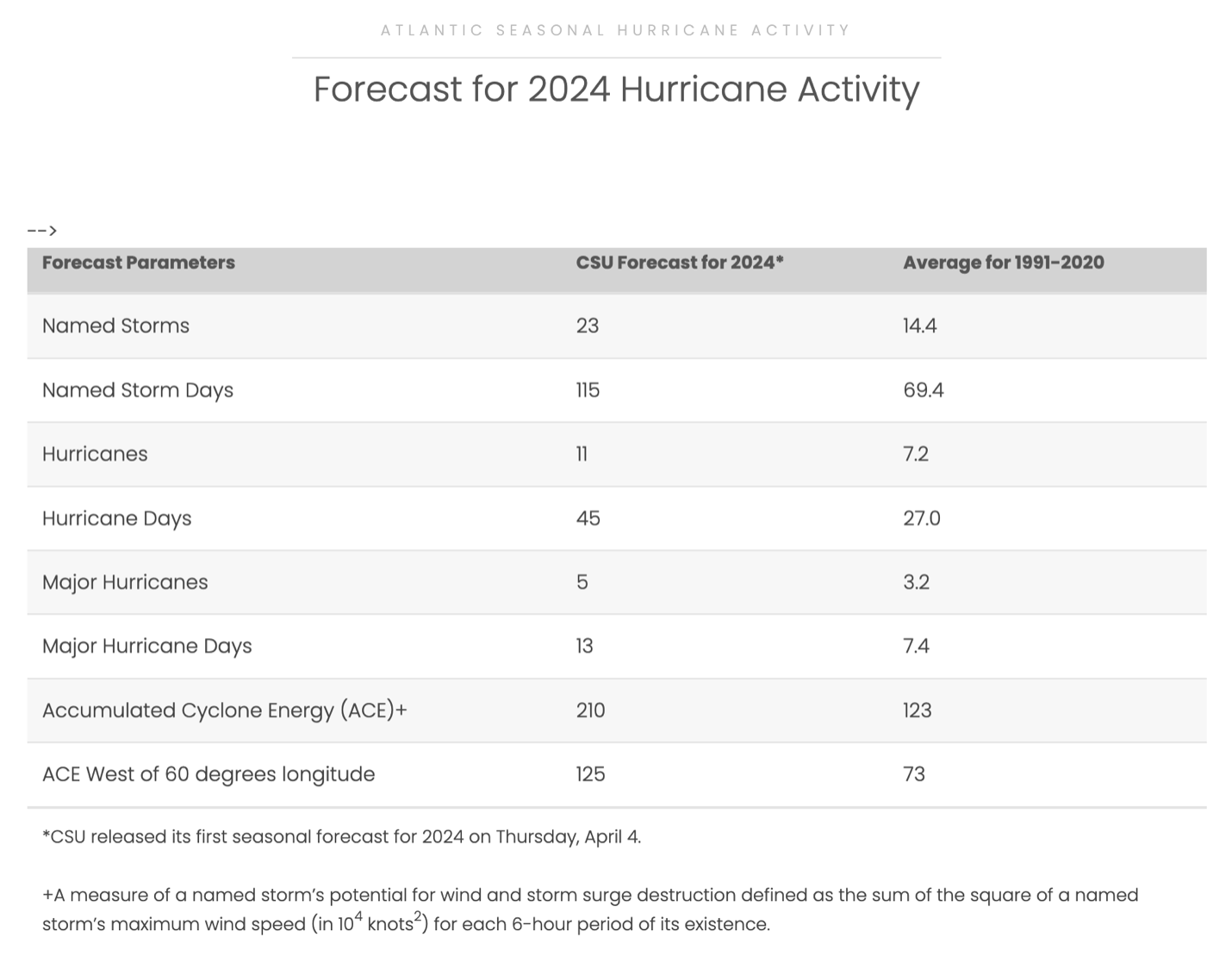

As we trek through the month of April, the hurricane season in the North Atlantic is fast approaching. Particularly, conditions in the Atlantic Ocean are looking textbook-favorable for a hyperactive season [1]. Colorado State University (CSU), which has been issuing tropical cyclone (TC) seasonal outlooks since 1984, recently released their April predictions for the 2024 Atlantic hurricane season [1]. The agency’s first forecast for the season calls for 23 named storms, 11 hurricanes, and 5 major hurricanes to form in the Atlantic during 2024 [1]. The full forecast summary is displayed in Figure 1. It should be noted that this is the most active April outlook ever released by CSU since they started issuing seasonal outlooks of TC activity. In this blog post, we plan to look at some of the major players driving these forecasts of hyperactivity, as well as what this could mean for your assets this hurricane season.

Figure 1: Colorado State University’s April forecast for 2024 Atlantic hurricane activity. Full forecast available at: https://tropical.colostate.edu/forecasting.html.

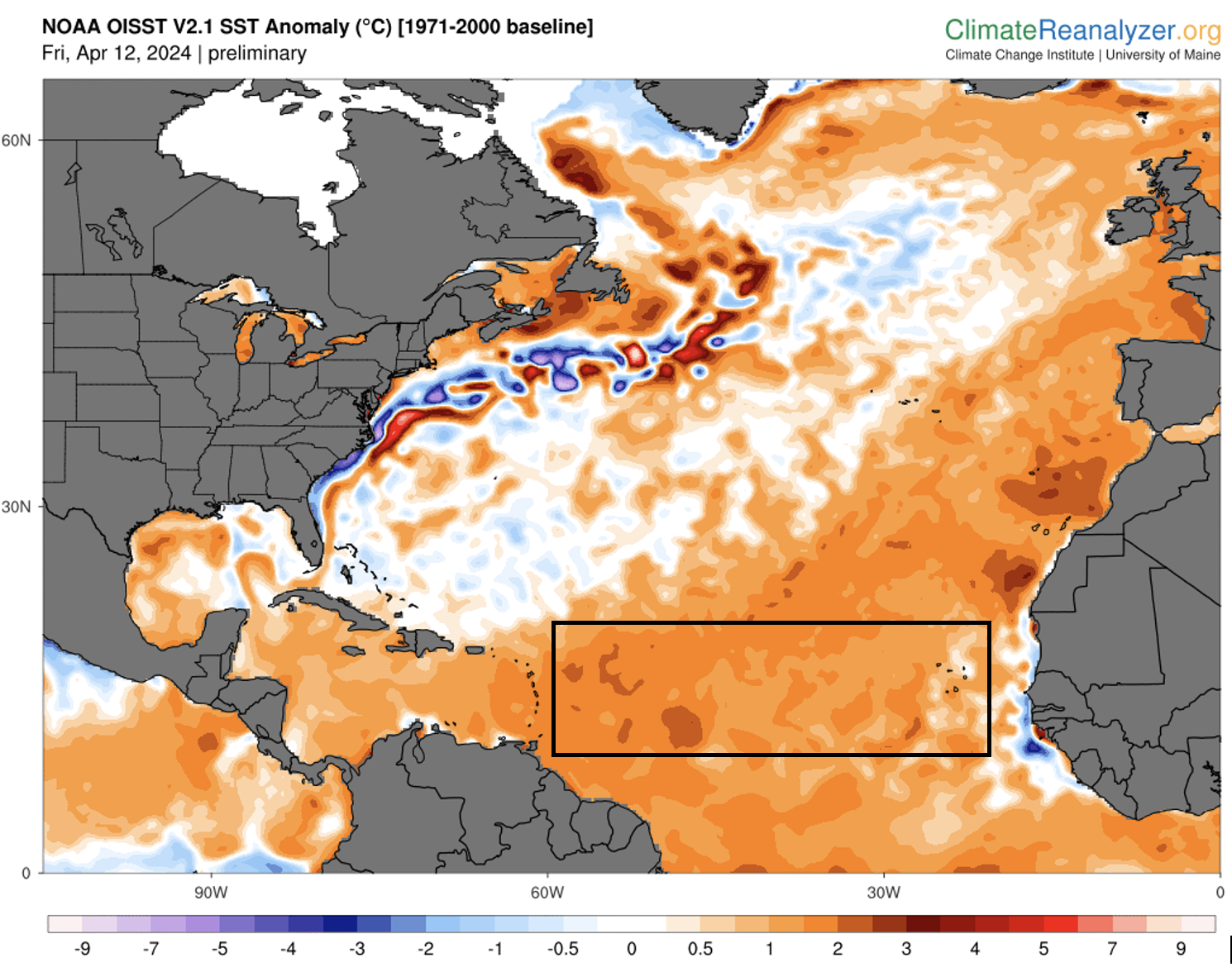

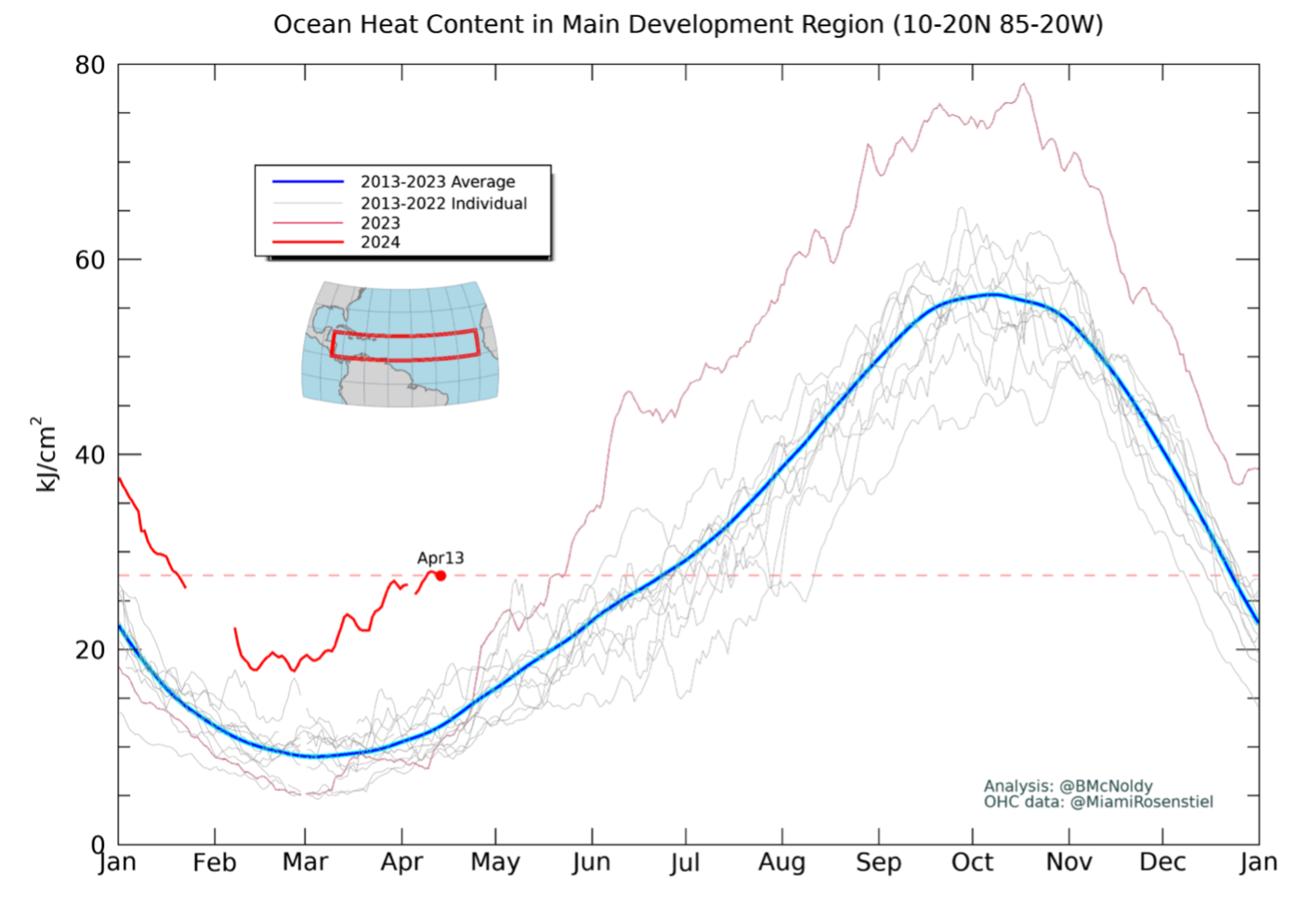

The first contributing factor the group looked at is sea-surface temperatures (SST) throughout the tropical Atlantic and Main Development Region (MDR) [the Main Development Region refers to the area of the North Atlantic Ocean bounded between 10-20° N and 20-60° W where about 75% of all major hurricanes develop from disturbances coming off the coast of Africa [1, 2]. SSTs are not only running 1 to 2 degrees Celsius above normal throughout much of the tropical north Atlantic and Caribbean (Figure 2); they are also well above the SSTs of any previous year within the last decade for this time of year [1, 3, 4]. In fact, when comparing the latest SST reading on April 13 in Figure 3 to the average of the previous decade, one can conclude that the current ocean heat content throughout the tropical Atlantic is more characteristic of the month of July. 2024 is also ahead of the SSTs from this time last year (recall that 2023 featured several months of record-breaking warmth throughout the tropical Atlantic Ocean) [4, 5].

Figure 2: SST anomalies for the Atlantic Ocean from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration valid Friday, April 12, 2024. The approximate location of the Main Development Region is boxed in black. Image borrowed from ClimateReanalyzer.org.

Figure 3: Ocean heat content in the Main Development Region for the last decade of data. The red line shows the current year (2024). Image borrowed from https://bmcnoldy.earth.miami.edu/tropics/ohc/

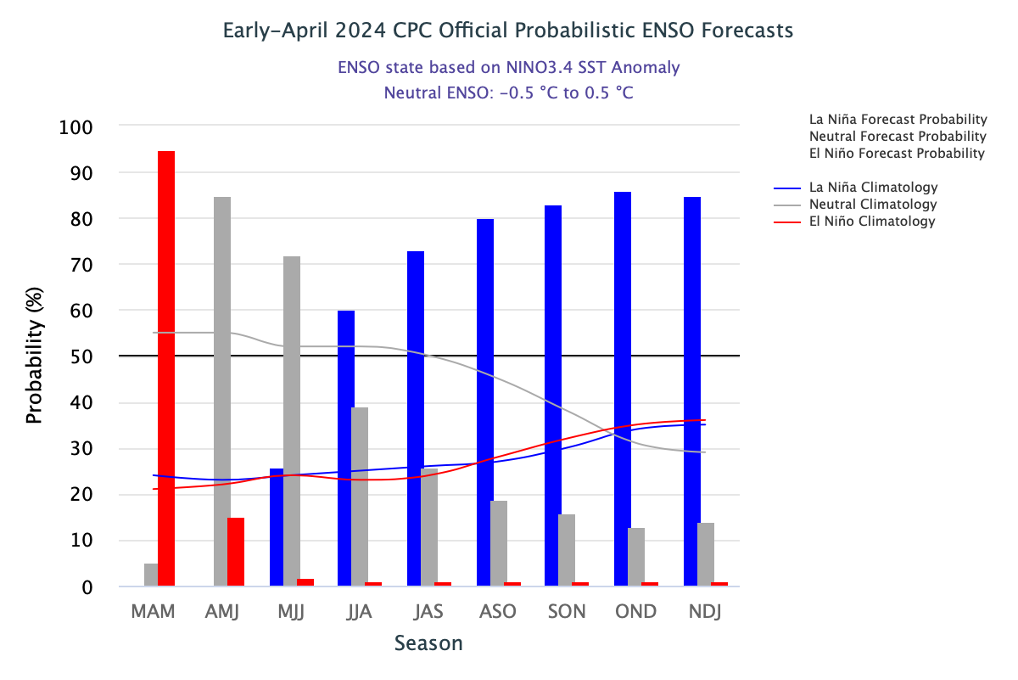

The second major factor favoring a hyperactive Atlantic hurricane season is the transition to neutral and, if forecasts are correct, eventually La Niña conditions in the equatorial Pacific by the peak of the hurricane season (August-September-October) [1, 6]. El Niño is associated with greater wind shear over the Atlantic and Caribbean, which provides a hostile environment that acts so suppress TC formation [9]. The potential switch to La Niña by the summer implies that this prohibiting factor would likely be removed.

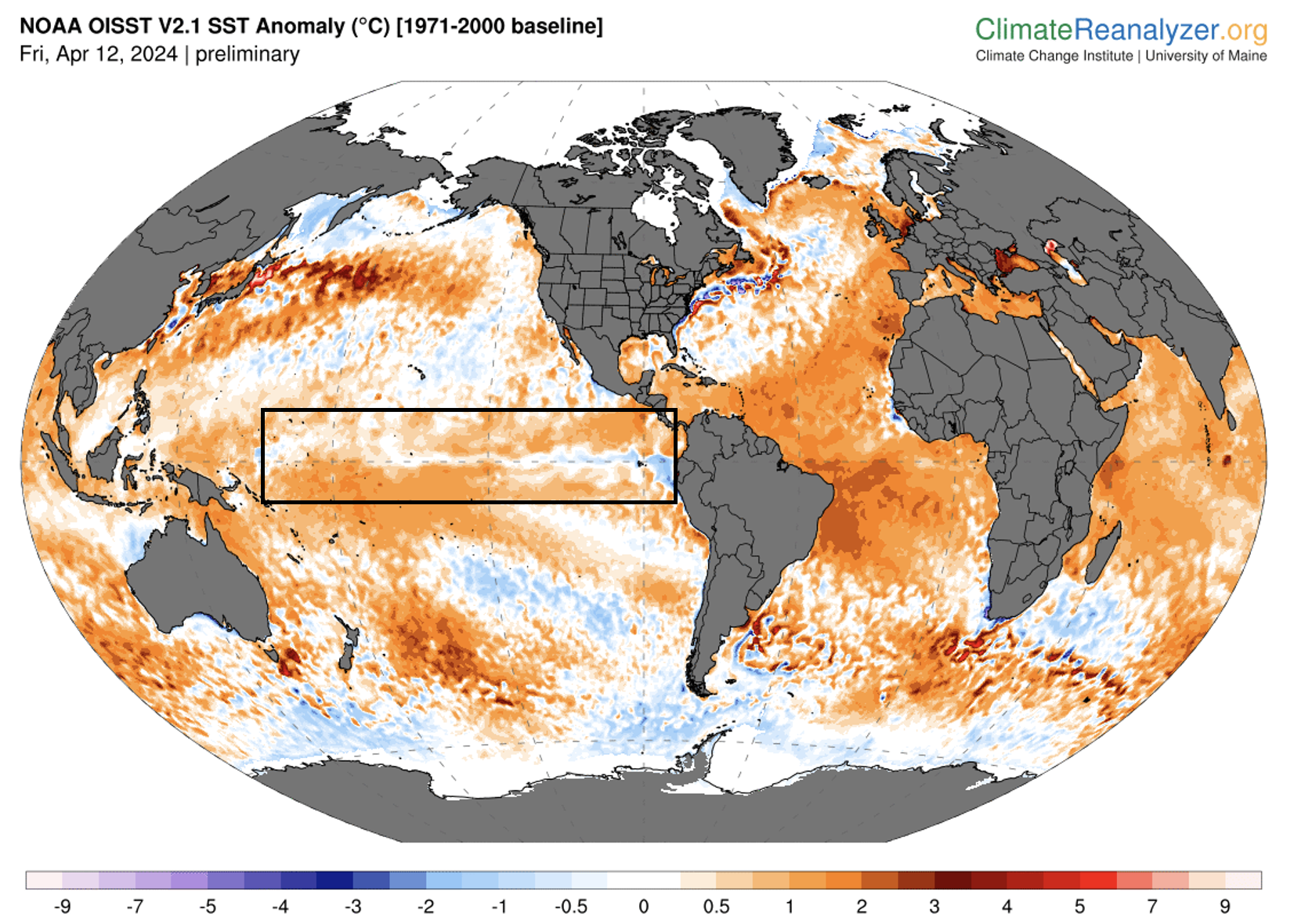

Figure 4 shows the current SST anomalies for the globe with the equatorial Pacific boxed in black. We see that some below-average SSTs (blue shading) have emerged over the parts of the equatorial Pacific. Though El Niño conditions remain, Figure 5 shows that El Niño is predicted to rapidly dissipate within the next month and a La Niña becoming highly likely by the summer. What else is striking in Figure 4 is how anomalously warm the Atlantic is compared to any other major ocean basin in the world for this time of year.

Figure 4: Global SST anomalies from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration valid Friday, April 12, 2024. Image borrowed from ClimateReanalyzer.org.

Figure 5: Percent probability of La Niña conditions (blue), El Niño conditions (red), and neutral conditions (gray) for composite monthly periods. Image borrowed from: https://iri.columbia.edu/our-expertise/climate/forecasts/enso/current/.

So, with a seemingly optimal setup for tropical cyclone development a growing likelihood, what could this mean for the overall hurricane season? Well first, it is important to note that just because conditions right now favor a hyperactive season does not mean that conditions can’t change by the peak of the season. We have seen past years, such as 2013, that were initially forecast to be hyperactive but that turned hostile for TC development by the peak of the summer [7]. However, this is generally uncommon and 2013 was seen as more of an exception to the rule that dumbfounded the hurricane forecasting community. Thanks to statistical models and our increased understanding of the factors leading to TC formation and strengthening, we can assume with a moderate level of confidence that the Atlantic will feature above normal activity this year, assuming that the present conditions and trends continue [1].

What remains less clear, however, is where the storms that do form will track. This area of forecasting is much less skillful, since predicting where hurricanes will go before they’ve even formed yet is incredibly difficult [1]. CSU did note in their forecast discussion that there is an above normal probability (compared to climatology) of a tropical storm/hurricane landfall for every part of coastline in the United States this year [1]. However, this is based on the principle that the greater number of storms that occur in a year, the usually greater likelihood that at least one of them will impact the United States [1]. This is not always the case, however. In 2010, for example, several major hurricanes formed but none of them directly impacted the United States [8]. In fact, no hurricanes impacted the United States that year [8]. Most of the storms in 2010 were long-tracked hurricanes that formed near Cabo Verde and were swept out to sea by persistent low-pressure areas over the East Coast of the United States in summer and fall of 2010 [8]. Because the key to predicting hurricane tracks lies in our ability to forecast the nature of these North American weather systems and their interaction with the Bermuda-Azores high, and because these systems aren’t able to be reliably predicted more than a week in advance, our ability to say just which/if any land areas will see impacts before a storm forms is next to impossible [8].

With that being said, it’s important to prepare for any hurricane season as if it will be the year you will be affected. The seasonal forecasts, in a sense, mean little with regards to your impact in any given year. It takes only one major hurricane to cause billions of dollars to property and a prodigious loss of life, even in an inactive season. A classic example is the 1992 Atlantic hurricane season, there were only 7 storms of tropical storm strength or greater, yet Hurricane Andrew, an historic Category 5 storm, struck the Miami area and caused one of history’s most costly hurricane events in the US.

Here at Kinetic Analysis Corporation, it’s our job to make sure you are prepared before disaster strikes. We’ve recently upgraded our web app, KinetiCast™, to allow users to upload their own assets and receive alerts in real-time (up to 5 days in advance) whenever their properties are forecast to be impacted. These alerts include information such as the estimated loss to the structure and its contents, the estimated shutdown/evacuation time, and the downtime in days. This type of critical information could be just what you need to protect your business, alert as many of your clients to oncoming hazards, and protect as many lives and as much property as possible. For more information about the plans and data we offer, please reach out to aagastra@kinanco.com.

References

1. https://tropical.colostate.edu/forecasting.html

2. https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/people/wd51hd/vddoolpubs/AMS_Jclim_2006_6005-6024_AtlanticinfluenceonNorthAmerica.pdf

3. https://climatereanalyzer.org/clim/sst_daily/

4. https://bmcnoldy.earth.miami.edu/tropics/ohc/

5. https://yaleclimateconnections.org/2023/11/the-unusual-2023-atlantic-hurricane-season-ends/

6. https://iri.columbia.edu/our-expertise/climate/forecasts/enso/current/.

7. https://tropical.atmos.colostate.edu/Includes/Documents/Publications/2013season_short.pdf

8. https://www.weather.gov/bro/2010event_hurricaneseasonwrap

9. https://www.weather.gov/jan/el_nino_and_la_nina#:~:text=El%20Ni%C3%B1o%20produces%20stronger%20westerly,a%20healthy%20circulation%20can%20form.