January 2025 Warmest on Record for the Globe, 1.75 °C Above Pre-Industrial Levels

An analysis of the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts’ 5th generation reanalysis data (ERA-5) shows that January 2025 was the warmest on record globally [1]. Incredibly, this is despite a strengthening La Niña event in the equatorial Pacific Ocean [1, 2, 3] which is generally associated with a moderation of global temperatures. Before we dive into the implications, let’s first look at some of the regional patterns of temperature anomaly across the globe.

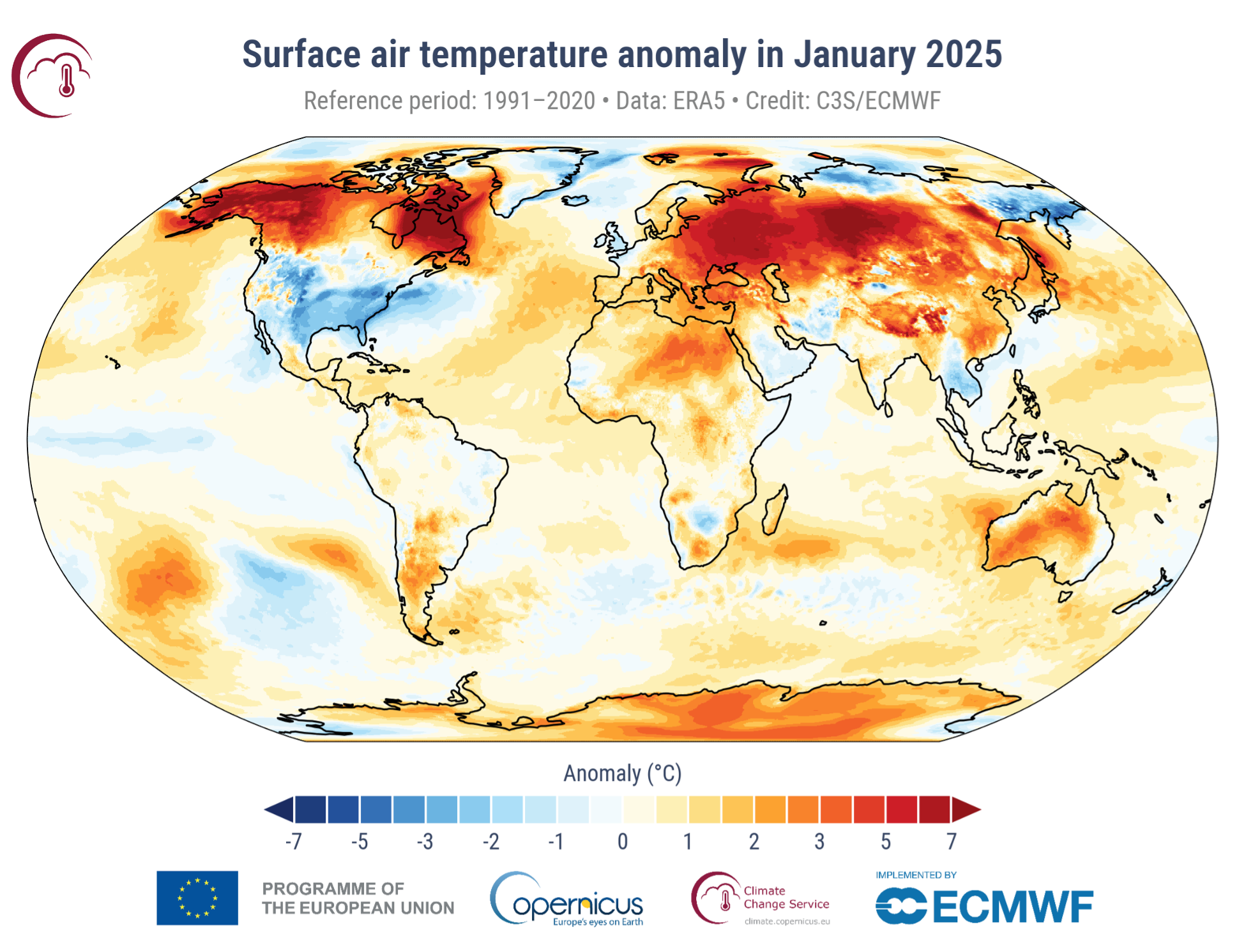

Figure 1: Surface air temperature anomaly for January 2025 relative to the January average for the period 1991-2020. Data source: ERA5. Credit: C3S/ECMWF.

Figure 1 shows that, much of the globe, particularly high-latitude regions such as Alaska/Canada, northern Europe, and Siberia saw the highest temperatures relative to the 1991-2020 mean [1]. These patterns generally support what scientists have known for years – high latitude continental spots, particularly during winter months, are warming much more rapidly than equatorial regions [5]. However, large parts of the contiguous United States, thanks to a series of Arctic outbreaks and rare snowfall across the South, saw temperatures below average [4].

Figure 2 shows monthly global surface air temperature anomalies from ERA5, using the pre-industrial period (1850-1900) as a reference [1]. The graph confirms that January 2025 was the warmest January on record globally relative to the pre-industrial period. In addition, the graph shows that 2024 had the previous warmest January and that annual average of the prior two years (2023 and 2024) were also the warmest on record. Only time will tell if 2025 and subsequent years will continue to break temperature records. But what makes the warming since 2023 noteworthy, and what might be the associated consequences?

Figure 2: Monthly global surface air temperature anomalies from ERA5, calculated using the pre-industrial period (1850-1900) as the reference.

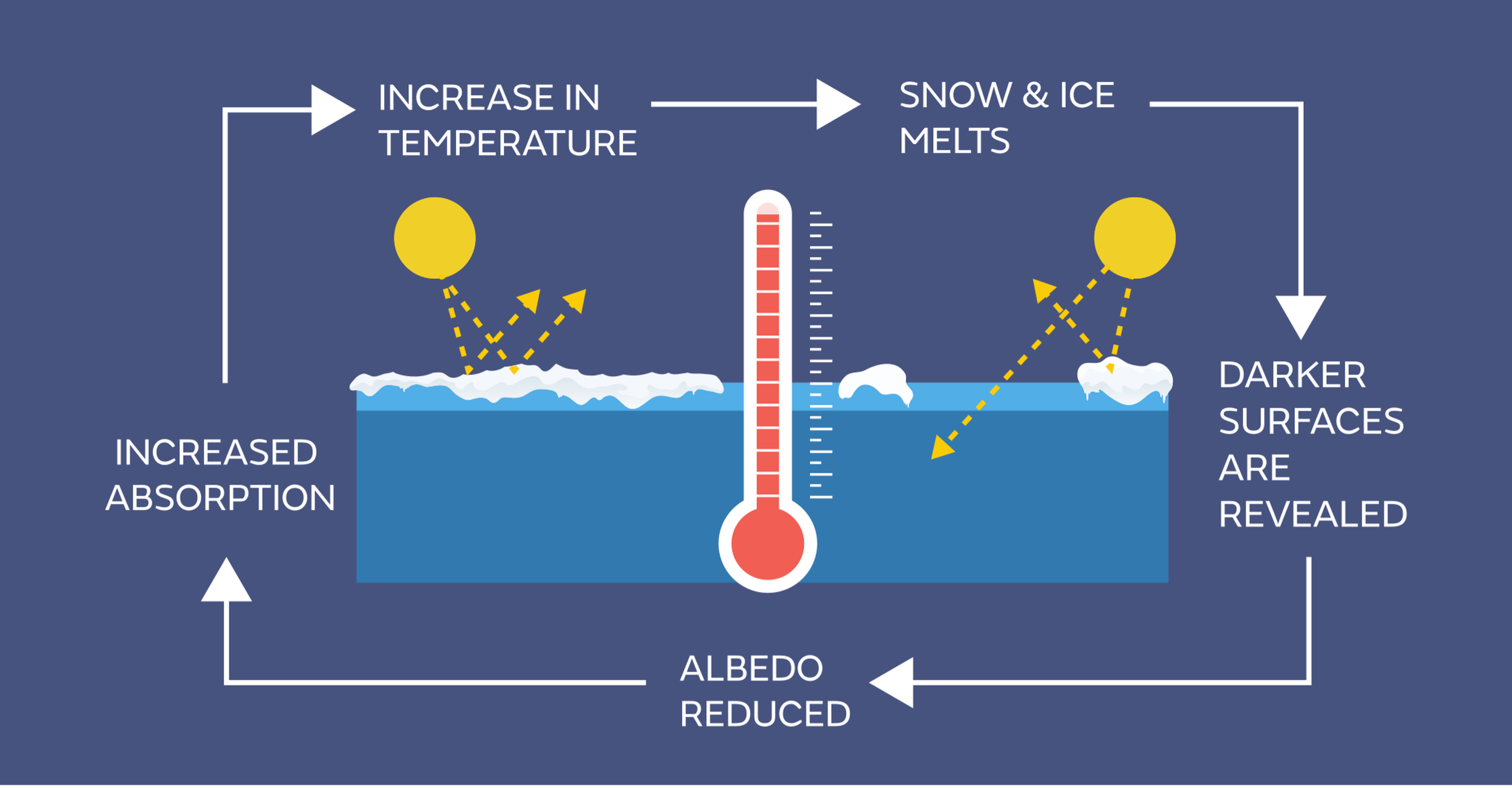

Scientists have emphasized the importance of keeping overall global warming well below 2 degrees Celsius, with the Paris Climate Agreement citing 1.5 degrees as the more aggressive goal [6]. Beyond this point, scientists believe that the risk of extreme weather events like droughts, heatwaves, floods, heavy precipitation, and wildfires will significantly increase [6, 7]. Both 2023 and 2024 featured several months with temperatures above this critical temperature threshold. In addition, some scientists believe that surpassing this threshold of warming could lead to irreversible climate tipping points, such as rapid melting of polar ice sheets and permafrost. Because ice largely reflects solar radiation, it provides a cooling mechanism for the atmosphere [6, 7, 8]. However, if the ice melts, the open ocean is exposed. Since the ocean absorbs radiation much more than it reflects it (which can be seen in the darker color of ocean water as compared to ice), this no longer provides the cooling mechanism to keep the atmosphere closer to equilibrium.

The above is what’s known as a positive feedback loop in climate science – whereby one, initial disturbance (in this case, warmer temperatures resulting in the melting of ice sheets) enhances the original response (climate warms further due to increased radiative absorption by the Earth’s oceans, resulting in further ice melt) [9]. Positive feedback such as this make scientists concerned about what future climate may look like if such tipping points are crossed.

Figure 3: Schematic explaining the feedback loop that results when an increase in temperature results in greater snow/ice melt. The albedo is the percentage of solar radiation that is reflected. A higher albedo indicates a higher reflectivity, whereas a lower albedo means that more of the solar radiation is being absorbed by the surface and thus converted to heat energy. Image borrowed from: https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/research/climate/cryosphere-oceans/sea-ice/index

Take the case of permafrost, which is soil, rock, or sediment that remains frozen for at least two years [10]. When it melts, it released carbon into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide and methane. While carbon dioxide is the main contributor to global warming, methane is an even more potent greenhouse gas; in fact, it is more than 28 times as potent as carbon dioxide at trapping heat in the atmosphere [11]. Thus, the melting of permafrost is another positive feedback that enhances existing climatic warming. Recent data also indicate that clouds/storm bands in Earth’s atmosphere may be shrinking, allowing more solar radiation to hit the Earth’s surface [12]. While this mechanism is poorly understood, it could be yet another feedback resulting in the amplification of global climate change.

With all this in mind, have we surpassed the threshold? With both 2023 and 2024 being the warmest on record globally, featuring several months with an average temperature above 1.5°C relative to the pre-industrial, could this be a sign of more significant consequences to come?

The climate system is an intricate network of interrelated networks and spheres. There remains significant uncertainty in what future climates will look like, with this largely depending on efforts to slash greenhouse gas emissions over the next several decades [13]. However, despite the alarming signal presented the last couple of years, it is never too late to prevent more significant future damage. History has shown that cooperation among several countries and entities can make a dramatic difference on the health of our planet. For example, the passing of the Montreal Protocol in 1989 was an international agreement to phase out ozone-depleting substances known as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) [14]. It was the first and one of the only treaties to be universally ratified by all United Nations member states [14], a rare example of what happens when countries and entities from around the world come together for a joint interest. Thanks to the passage of the protocol, CFC’s were dramatically reduced, resulting in a shrinking of the ozone hole since its peak size in the early 2000’s [15].

It’s important to recognize that when we talk about the health of the planet, what we’re really discussing is the health of the people. A healthy, sustainable planet leads to a healthy human population and allows us to pass that legacy on to future generations. And it is never too late to work toward a healthy, bright future.

References

2. https://wmo.int/media/news/january-2025-sees-record-global-temperatures-despite-la-nina

4. https://weather.com/news/weather/news/2025-02-10-coldest-january-us-since-1988-earth-warmest-noaa

5. https://www.nature.com/articles/s43247-022-00498-3

6. https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement

7. https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/science/climate-issues/degrees-matter

8. https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/research/climate/cryosphere-oceans/sea-ice/index

9. https://gml.noaa.gov/education/info_activities/pdfs/PSA_analyzing_a_feedback_mechanism.pdf

10. https://www.nature.com/articles/s43017-021-00230-3

11. https://www.epa.gov/gmi/importance-methane

12. https://www.science.org/content/article/earth-s-clouds-are-shrinking-boosting-global-warming

14. https://www.unep.org/ozonaction/who-we-are/about-montreal-protocol